The U.S Court of Appeals for the Fourth Circuit has vacated the FLANAX decision of the U.S. District Court for the Eastern District of Virginia (here), and has remanded the case to the district court for further proceedings. The lower court had dismissed Bayer’s Section 43(a) false association and false advertising claims under FRCP 12(b)(6) and had entered judgment on the pleadings as to Bayer’s Section 14(3) claim, based on the district court’s reading of the Supreme Court’s Lexmark decision. Belmora LLC v. Bayer Consumer Care AG and Bayer Healthcare LLC, Appeal No. 15-2335 (March 23, 2016) [precedential].

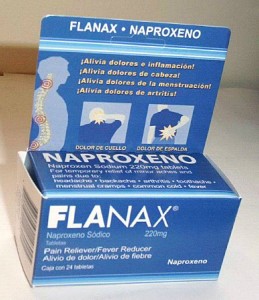

Belmora’s FLANAX

[Caveat: as co-counsel to Belmora on this appeal, I will confine this post to a brief overview of the decision, leaving it up to my dear readers to absorb the entire opinion].

The district court ruled that the Lanham Act does not allow an owner of a foreign mark not registered in the United States, who does not use the mark in the United States, to assert priority rights over a mark [FLANAX] that is registered and used by another party [Belmora] in this country.

The Fourth Circuit concluded that the district court misapplied the Lexmark ruling:

The primary lesson from Lexmark is clear: courts must interpret the Lanham Act according to what the statute says. To determine whether a plaintiff, “falls within the class of plaintiffs whom Congress has authorized to sue,” we “apply traditional principles of statutory interpretation.” Id. at 1387. The outcome will rise and fall on the “meaning of the congressionally enacted provision creating a cause of action.” Id. at 1388.

The Fourth Circuit observed that there is no requirement in the language of Section 43(a) that a plaintiff must have used its own mark in commerce. The district court erred in requiring Bayer to have pled use of its own mark in commerce “when it is the defendant’s use of a mark or misrepresentation that underlies the Section 43(a) unfair competition cause of action.”

Section 43(a) claims: The appellate court then applied Lexmark and found that Bayer’s claims of unfair competition falls with the Lanham Act’s protected zone of interests, and that Bayer pleaded “proximate causation of a cognizable injury.” Bayer claimed that Belmora’s “misleading association with BCC’s FLANAX has caused customers to buy the Belmora FLANAX in the United States instead of purchasing BCC’s FLANAX in Mexico.” In short, BCC lost sales revenues in Mexico.

The Fourth Circuit concluded that Bayer adequately pled a Section 43(a) claim, the allegations reflecting the Lanham Act’s purpose of preventing “the deceptive and misleading use of marks” in “commerce withing the control of Congress.”

As to proximate cause, Bayer alleged lost sales in Mexico, and so Bayer may plausibly claim damages from Belmora’s allegedly deceptive use of the FLANAX mark.

At this inital pleading stage, the court must draw all reasonable inferences in Bayer’s favor. It concluded that Bayer sufficiently pled a false association cause of action under Section 43(a).

Bayer also alleged a false advertising claim under 43(a), and this claim also falls within the Lanham Act’s zone of protection. Belmora’s allegedly deceptive advertising could have resulted in U.S. customers Belmora’s FLANAX instead of Bayers’ ALEVE brand product. These lost customers satisfy the requirement of injury proximately cause by the challenged conduct.

The appellate court therefore concluded that the Lanham Act allows Bayer to proceed with its Section 43(a) claims. However, the court noted, Bayer must still prove injury proximately caused by Belmora’s conduct.

The Board noted that it did not conclude that Bayer “has any specific rights in the FLANAX mark” in the United States. Belmora owns the mark. But Belmora may not use the mark “to deceive customers as a source of unfair competition.” It is up to the district court to fashion an appropriate remedy.

Section 14(3): Again applying Lexmark, the Board agreed with Bayer that Section 14(3) of the Lanham Act, which permits cancellation of a registration for a mark that is being used to misrepresent source, does not include a use requirement, and such a requirement cannot be read into that section. Thus the district court erred in reversing the TTAB’s decision ordering cancellation of the FLANAX registration.

The appellate court remanded the case to the district court for further proceedings consistent with its opinion.